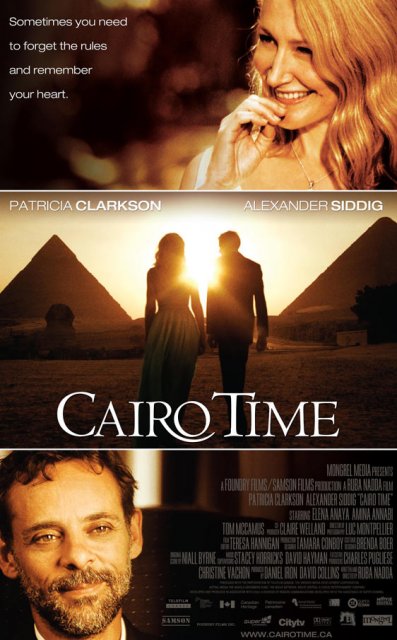

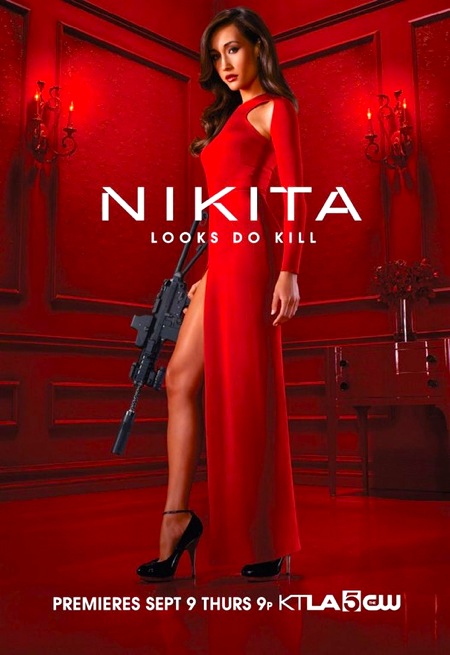

By Jason Apuzzo. Does the poster on your left grab your attention? It certainly caught mine, although perhaps that had to do with the fact that there was an approximately 100 foot high version of it draped over a building I drove by recently here in LA. I have a great interest in firearms, you understand, and seeing an automatic rifle that large immediately caught my attention.

By Jason Apuzzo. Does the poster on your left grab your attention? It certainly caught mine, although perhaps that had to do with the fact that there was an approximately 100 foot high version of it draped over a building I drove by recently here in LA. I have a great interest in firearms, you understand, and seeing an automatic rifle that large immediately caught my attention.

I’m being facetious, of course – at least with respect to the relative appeal of firearms. Nikita, for those of you who may not have heard, is the CW’s reboot of a TV show – La Femme Nikita – that was actually once run by an acquaintance of mine, 24 producer Joel Surnow. And Joel’s show, in turn, was based on the 1990 Luc Besson film of the same name, about a young criminal babe recruited to work for French intelligence – and to otherwise fire guns while wearing 4-inch heels.

There was a so-so American remake of Besson’s film that followed in 1993, called Point of No Return, starring Bridget Fonda. Then came Joel’s gritty, noirish and very successful show in the late 90s – until that show ran its course, roughly around the time he was developing 24.

And whereas the specific plotlines of these various Nikitas have changed, one element has remained constant: a sexy young misfit woman, who must be able to fire semi-automatic weaponry while wearing cocktail dresses, is recruited by mysterious intelligence forces to fight … somebody.

Perhaps you already see where I’m going with this.

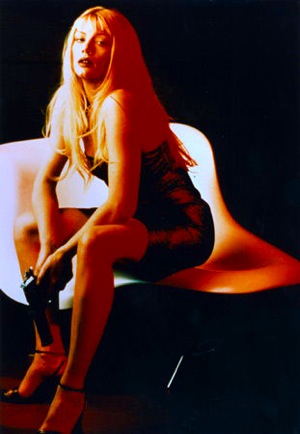

In Joel’s version of La Femme Nikita, sexy young Nikita (played by Peta Wilson) is recruited by a shadowy government organization to fight terrorism. [Bear in mind that this anti-terrorist plotline was developed prior to 9/11 – as was 24‘s original plotline, incidentally.] Some of La Femme Nikita’s basic plotline and vibe eventually got rolled into 24 – with fantastic results, of course.

Now would seem to be a good time to go back to that anti-terror storyline, what with Al Qaeda still lurking around, right? With, for example, young terrorist guys trying to set off bombs in Time Square, or gals like Jihad Jane trying to recruit young people into Al Qaeda.

And incidentally, let’s not forget Salt in this context. In that very recent film, sexy spy Angelina Jolie battles retro-communist sleeper agents here in the U.S. – in a clever, Rubik’s Cube storyline seemingly ripped from current headlines (i.e., the capture of Russian spy babes like Anna Chapman and Anna Fermanova). The worldwide grosses on Salt are currently topping $150 million, so now would seem to be a good time to send Nikita after some infiltrating, ideologically driven baddies, yes? Russian agents … Al Qaeda moles … perhaps even a Chinese communist superspy or two (cue Hawaii Five-O theme).

Wrong! In the new Nikita series, we’re the villains. Or at least, the C.I.A. and American intelligence services are the villains (see here and here or the video below). Angry, pinch-faced W.A.S.P. bureaucrats in cheap suits are the villains. [And I’ll bet they have bad aftershave, too!]

This irritates me. I would like to be able to watch this show, for reasons I presumably don’t need to explain (at least to the male readers of this website). Doing a series like this should be so easy – a breeze, actually.

You find some good looking gal, and have her hunt down, say, a snarling member of the A.Q. Khan smuggling network who’s trying to get nuclear materials into Miami … while he enjoys a few martinis at the Skybar. Maybe he’s a Russian mobster with a weakness for Incan quinoa and Fantasy Football.

Our delectable heroine pulls up to the club in a Lamborghini Murcielago (CUT TO: camera capturing her shapely leg as the doorman helps her out of the car); after some perfunctory banter, and few snappy and/or inane quips (“Next time, make sure my salmon is served cold!”) she pulls a Glock out of her garter and has a shootout with the Russian and his gang, and escapes from a fireball or two – just in time to make it back home to her charmingly oblivious boyfriend in the suburbs, who just got back from a sale at Ikea.

I mean, the story writes itself.

Instead, the CW has decided to make us the villains. What a drag. These kinds of shows are being made all the time (e.g., Alias, Dark Angel, Painkiller Jane), and there are many different ways to go with the material. CW is making the most idiotic decision imaginable by making our own intelligence services into the bad guys.

Why idiotic? Because your garden variety Hollywood liberal – one thinks here of, say, Jeffrey Wells – isn’t going to watch this series anyway just because there’s a snarky, leftie-conspiratorial plotline. They’ll consider this show too déclassé to begin with … while potential viewers like me get alienated. And again, why? What’s the purpose? Because the producers want to make some asinine point about U.S. foreign policy?

Is that really why they think we watch this stuff?

Posted on August 10th, 2010 at 1:57pm.